From Mao to Markets: China’s Economic Journey Since 1949

Maoist Era (1949–1976)

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Mao Zedong implemented a Soviet-inspired centrally planned economy, prioritizing heavy industry and collectivized agriculture.

The Great Leap Forward (1958–1962) aimed to rapidly industrialize but led to catastrophic famine, with grain output collapsing by up to 30% in key years.

The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) disrupted education, industry, and governance, slowing economic progress, though infrastructure projects like the “Third Front” boosted industrial bases in China’s interior.

Reform and Opening Up (1978–1990s)

After Mao’s death, Deng Xiaoping launched reforms in 1978, shifting toward “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Key policies included:

Household Responsibility System: Farmers could sell surplus crops, boosting agricultural productivity.

Special Economic Zones (SEZs): Cities like Shenzhen became hubs for foreign investment and export-led growth.

Gradual Market Liberalization: State-owned enterprises were restructured, and private businesses began to flourish.

These reforms triggered unprecedented growth, lifting millions out of poverty and integrating China into global trade networks.

Global Integration (2000s–2010s)

China’s WTO accession in 2001 marked a turning point, opening markets and accelerating exports.

The country became the “world’s factory,” dominating global supply chains in electronics, textiles, and manufacturing.

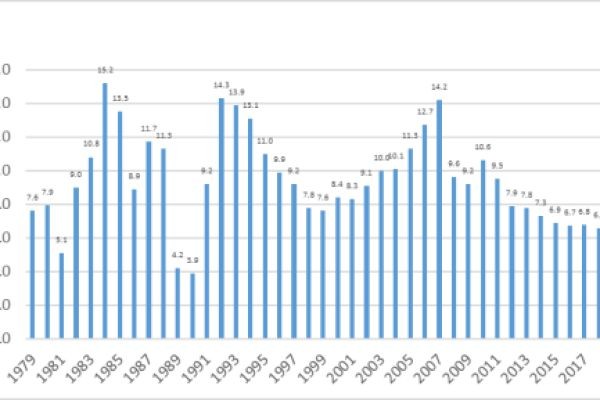

Massive infrastructure projects, urbanization, and foreign direct investment fueled GDP growth rates averaging 10% annually for decades.

By the 2010s, China had become the second-largest economy in the world, reshaping global trade and finance.

Challenges in the 21st Century

Debt and Overcapacity: Heavy reliance on investment-led growth created inefficiencies.

Demographic Shifts: An aging population threatens long-term labor supply.

Geopolitical Tensions: Trade disputes, especially with the U.S., highlight vulnerabilities in global integration.

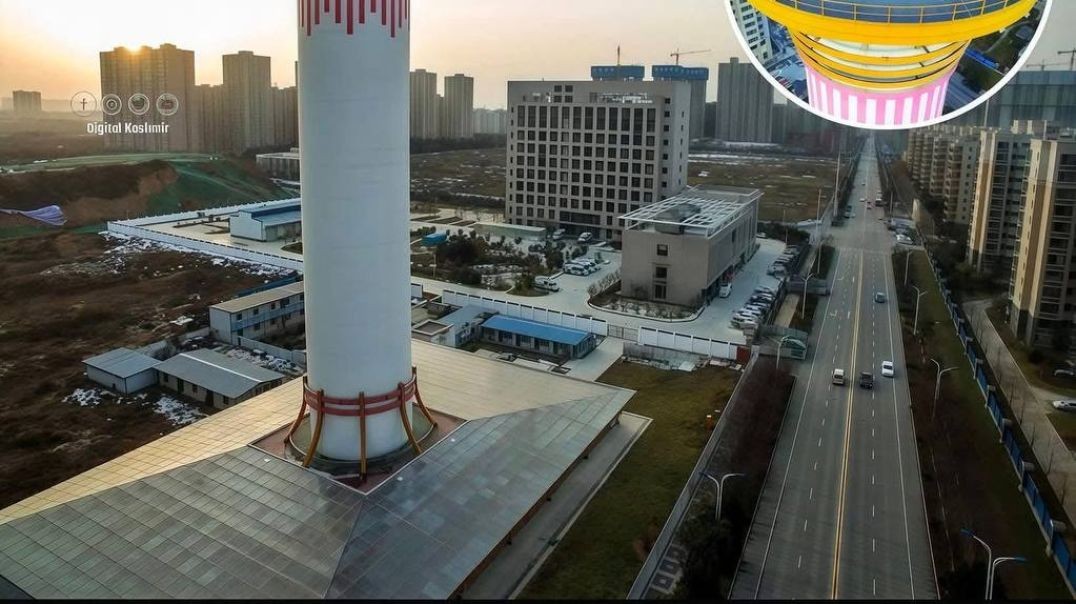

Environmental Concerns: Rapid industrialization has led to pollution and sustainability challenges.

The Future: Balancing State and Market

China is now focusing on innovation, green energy, and digital transformation to sustain growth.

Policies emphasize “dual circulation”—boosting domestic consumption while maintaining global trade.

The challenge lies in balancing state control with market dynamism, ensuring stability while fostering creativity and competitiveness.

Conclusion

China’s journey from Mao to markets is unparalleled in modern history. From famine and upheaval to prosperity and global influence, the country’s economic evolution reflects resilience, adaptability, and ambition. As China faces new challenges, its ability to balance tradition with innovation will determine the next chapter of its economic story.